Being great at your job doesn’t automatically mean you’re great at social gatherings. I can teach confidently all day, but a lively farewell party leaves me internally awkward and counting the minutes until I can leave. Here’s an honest look at why competent professionals can still feel awkward at office parties, and why it’s more common than people think. And no, this isn’t about being ungrateful or unfriendly; it’s simply how many introverts are wired.

Understanding the Gap Between Professional Confidence and Social Anxiety

Table of Contents

Why Competent Professionals Feel Awkward at Office Parties

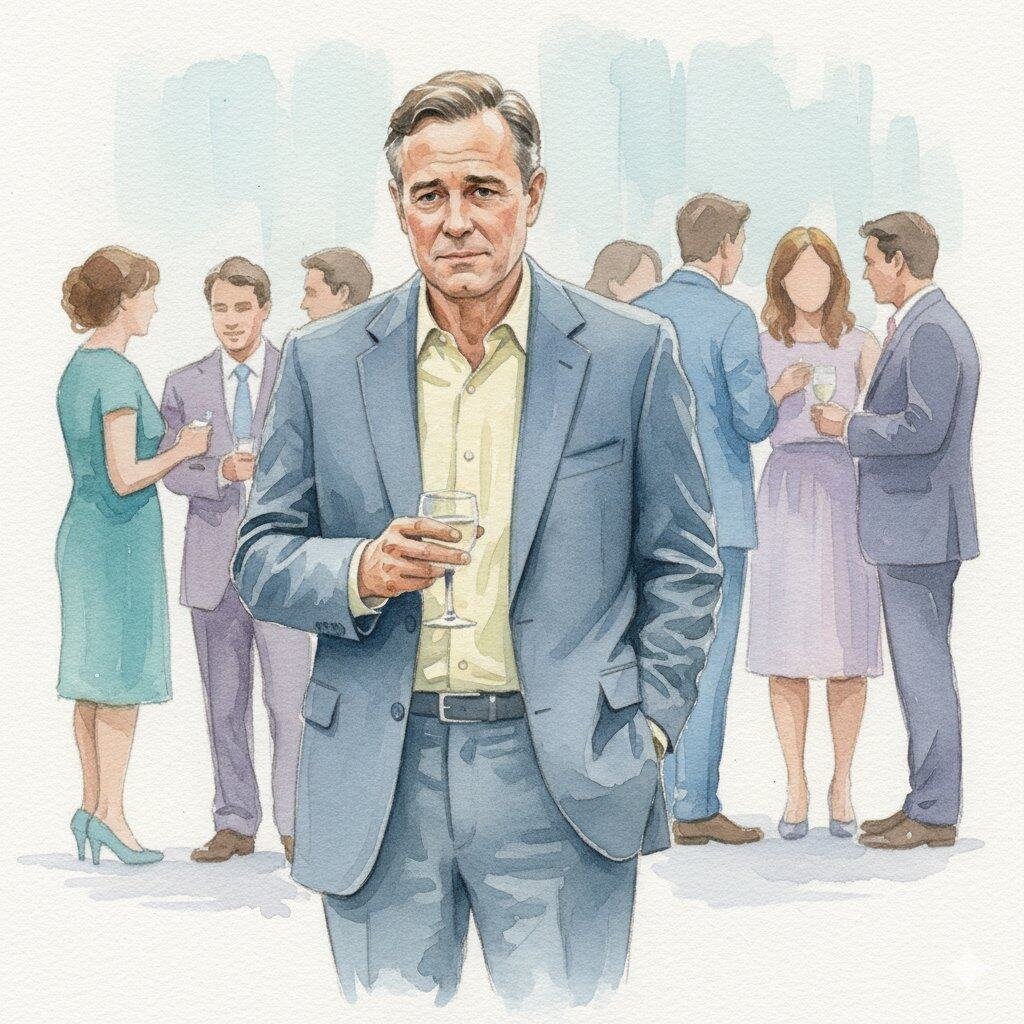

Last week, I attended a drinking gathering to mark the closing of one of the schools where I worked. Sixteen years of teaching, countless students, colleagues from various companies and groups, all gathered in a lively venue for a meaningful farewell to mark our time together.

I teach English. Stand in front of classrooms regularly. Engage with students about their dreams, correct their grammar, encourage them through difficult concepts. In that professional setting, I’m completely comfortable. Confident, even.

But put me in that crowded room with a beer in my hand and a social obligation to mingle? Internally awkward. Uncomfortable in ways that have nothing to do with the people or the occasion and everything to do with the setting itself.

I hadn’t been to a gathering for a while. And I’m clearly getting old. Surprisingly, I noticed that it was difficult to hear properly. The noise level made conversation tricky. As a teacher, you’re expected to walk around, engage everyone, be visibly present and positive. Some old faces offered a few compliments, and new contacts extending teaching opportunities. All genuinely nice interactions that I appreciated.

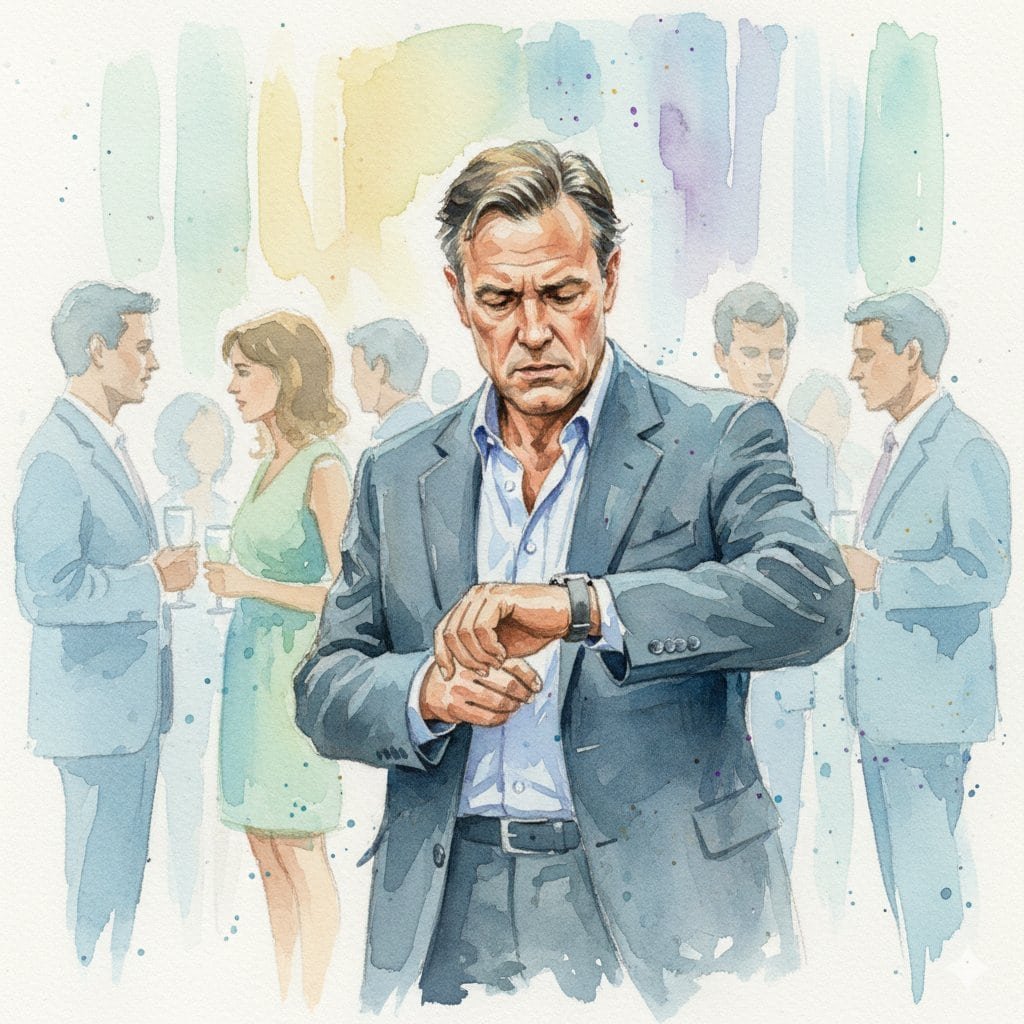

And yet I was relieved when the timing was right to leave.

Maybe some of the awkwardness came from it being my first event like this since my wife left last year. Not in a painful way, just in the sense that certain settings challenge us more than we admit when we’re learning to show up differently.

Do you ever feel completely competent professionally but socially uncomfortable in group settings?

The Split That Doesn’t Make Sense to Others

Here’s what confuses people: How can you be great with people professionally but awkward at office parties?

If you can stand in front of thirty students and teach with confidence, why does a social gathering bother you? If you’re comfortable one-on-one helping someone understand difficult concepts, how can small talk at a reception be a challenge?

The assumption is that social skills are universal. If you have them professionally, you should have them everywhere. But that’s not how it works for many people. For introverts especially, social comfort often depends entirely on context and structure.

Teaching has structure. Clear roles. Defined purpose. I know exactly what’s expected, and I’m good at delivering it. There’s a beginning, middle, and end. When the lesson finishes, so does my social obligation.

A drinking party? Stand here. Hold this drink. Mingle as duty requires. Make conversation with people you may not know well. Navigate the noise. Appear engaged and grateful (which you genuinely are) while your internal experience is counting down the minutes until you can politely leave without seeming awkward, rude or ungrateful.

It’s not about the people. It’s not about the occasion. It’s about the setting itself and the particular kind of social performance it requires.

What professional settings make you comfortable that social settings don’t?

The Work of Appearing Normal

The uncomfortable part isn’t just being there, it’s the constant internal monitoring.

Am I smiling enough? Too much? Am I standing in the right place? Should I move to another group? How long should I stay talking to this person before it becomes awkward? Am I standing too close because I can’t hear them? Am I holding my drink correctly? Why do I care about holding a drink correctly? Am I overthinking this? Yes, definitely overthinking this.

Meanwhile, professionally, none of this mental noise exists. In front of a classroom, I’m not monitoring my facial expressions or wondering if I’m standing in the right spot. I’m focused on the work, and that focus creates a kind of natural ease that social situations don’t always provide.

Some people find social gatherings energizing. Extroverts often thrive with more people and less structure. For introverts, depending on the occasion, it’s exactly reversed.

Neither is wrong. Neither is a character flaw. It’s just different wiring that shows up in different contexts.

What aspects of social gatherings specifically drain you?

When “Just Relax” Doesn’t Help

People who don’t experience this often offer well-meaning advice: “Just relax.” “Be yourself.” “Nobody’s judging you.”

But the discomfort isn’t logical. It’s not about believing people are judging me (much) or thinking I need to be perfect. It’s sensory, situational, and persistent regardless of how many times I tell myself it shouldn’t bother me.

The noise level that makes conversation difficult. The forced proximity to people I don’t know well. The lack of clear structure or endpoint. The restraint to not change the conversation. The social obligation to appear engaged when my natural preference would be to quietly observe from the edges.

These aren’t things you can think your way out of. They’re responses that happen regardless of your intellectual understanding that the situation is safe and the people are kind.

And they don’t disappear with age or experience. I’ve been teaching for twenty years. I’m comfortable with my professional skills. But put me in a drinking party setting, and the same internal awkwardness shows up that’s been there for decades.

If I dig deeper, it’s probably about roles. If you know your subject, you can hold your own and represent yourself. For example, giving a speech can be a challenge. But, if you have a passion, experience and knowledge of the subject, you feel a natural role to be there. You have something to offer. You belong. There’s no imposter syndrome.

The same thing might occur for any club, where the members all share a single passion to discuss. They know they belong, and the focus is on the passion.

Sometimes a social gathering with people you might not know, gives the role a greyer line – if that makes sense. Some people can feel awkward not quite knowing where they fit into the scenario. Maybe, it has something to do with physically standing still, which in itself is not particularly instinctive. People relax more when sitting down.

What well-meaning advice have you received that completely misses the point?

The Misconception About Growth

There’s an assumption that social discomfort is something you’re supposed to outgrow. That by your fifties, you should have developed the social ease that makes these situations effortless. For the most part, I believe this.

But for many people, what we’ve actually developed is better masking. We’ve learned to hide the discomfort professionally. To perform the expected social behaviors convincingly enough that most people don’t notice the internal strain.

That’s not the same as being comfortable. It’s just being skilled at appearing comfortable, which is its own kind of work.

The professional contexts where I’m genuinely at ease are teaching, one-on-one conversations about meaningful topics, and working alongside people toward a shared goal. Those remain comfortable. The obligatory social contexts, like standing around with a drink, making small talk, can remain draining.

What’s changed over the years isn’t the comfort level. It’s the acceptance that this is just how I’m wired, and the understanding that it’s okay to leave when the timing is appropriate rather than forcing myself to stay because “normal people” would enjoy it longer.

Has your social comfort level actually changed with age, or just your ability to hide the discomfort?

The Gratitude Alongside the Discomfort

Here’s what’s important to emphasize: None of this negates the genuine appreciation for the occasion, the people, or the opportunities that emerged from that gathering.

I’m grateful for the sixteen years at that school. Grateful for the students who showed up. Grateful for my boss and colleagues who wanted to mark the occasion together.

The internal awkwardness doesn’t diminish any of that gratitude. Both things can be true simultaneously, deeply appreciating the occasion while also feeling comfortable when it ends.

Sometimes, I worry that my lack of natural smiling in certain settings sends the wrong message. That people might interpret internal discomfort as disinterest or ingratitude. That’s not accurate, but I understand why the confusion might exist.

This is probably my way of subtly apologizing for any moments where my social discomfort might have appeared as something else. To anyone who’s ever extended kindness at a gathering and received a somewhat awkward response, it wasn’t about you. It was about me navigating a type of situation that’s always been challenging, regardless of how much I value the connection.

Have you ever worried that your social discomfort sends the wrong message about how much you care?

Finding Your Comfortable Contexts

What I’ve learned over the years: Find the professional and social contexts where you’re genuinely comfortable, and don’t judge yourself for struggling in others.

I’m good at teaching because the structure supports my strengths. I’m comfortable with one-on-one conversations because they allow for depth without performance. I value meaningful work alongside people more than casual socializing with crowds.

None of that makes me deficient at “being social.” It just means my social comfort has specific conditions that noisy drinking parties don’t meet.

For others, those conditions might be completely different. You might thrive in large group settings but struggle with one-on-one intensity. You might love casual social events but dread structured professional obligations.

Many introverts find that their social comfort requires specific conditions, like depth over breadth, structure over chaos, and purpose over performance.

The key isn’t forcing yourself into contexts that drain you or judging yourself for not enjoying what others seem to navigate effortlessly. It’s recognizing your genuine comfort zones and building a life that includes enough of those contexts to sustain you.

What contexts actually make you feel socially comfortable rather than socially drained?

The Permission to Leave

Perhaps the most valuable lesson: You don’t have to stay until the end of every social obligation just to prove you can handle it.

Show up. Be present. Engage genuinely within your capacity. And when you’ve fulfilled the reasonable expectations of the situation, give yourself permission to leave without guilt.

The right timing matters. You don’t want to leave so early it seems rude or dismissive of the occasion. But you also don’t need to stay until the last person goes home just to prove you’re “normal” or “social enough.”

For me, that night at the school closing gathering, the right timing came after I’d connected with old colleagues, received some kind words, engaged with the opportunities offered, and genuinely participated in marking the occasion. When I left, it wasn’t because I didn’t care. It was because I’d given what I had to give, and continuing to force it would have served no one. I also had work the next day.

That’s not social deficiency. That’s self-awareness and honest engagement within realistic limits.

How do you know when you’ve fulfilled your social obligation and can leave without guilt?

The Invitation to Honesty

This isn’t about complaining or seeking pity. It’s about naming something real that many people experience but rarely discuss openly.

If you’re great at your job but awkward at office parties, you’re not broken. If you can engage confidently in professional contexts but struggle at casual social gatherings, you’re not deficient. If you’ve reached your fifties and still find certain social situations challenging regardless of how many times you’ve experienced them, you’re not failing at adulthood.

Being an introvert doesn’t mean you can’t be social. It means your social energy works differently, and honoring that difference is self-awareness, not weakness.

You might be wired in a way that makes some contexts comfortable and others less so. Understanding that difference and building a life that honors it rather than fighting it might be more valuable than forcing yourself to enjoy situations that might never feel natural.

Do you feel awkward at office parties? Share your thoughts below. I respond to every comment, and your experience might help someone else.